Czech glass designers have been teaching as associate professors at TIGA – the Toyama City Institute of Glass Art, an internationally renowned educational institution in Japan, for thirty years.

Toyama (富山市 in Japanese), the capital of the eponymous prefecture, lies on the west coast of the Japanese island of Honshu. High mountains rising right behind the metropolis are well-known to the Czechs as they separate the Toyama Prefecture from the neighbouring prefecture of Nagano, where their ice hockey team won the Winter Olympics in 1998. In the 1980s, Toyama officials sought to promote, differentiate, and highlight their city to others. In the end, they chose to revive the then long-forgotten local production of pharmaceutical glass. Rather than returning to its factory production, they turned their attention to visually attractive art glass instead; a decision that was probably fuelled by the positive response received by the international glass competition repeatedly held in the nearby city of Kanazawa. The decision to build the modern prestige of the city of Toyama upon glass proved to be wise and far-sighted.

The goal of founding a glass educational institute and giving it an attractive program had been achieved in 1991, but that was only the beginning. Today, about 400,000 residents of the city as well as tourists are confronted with glass art in the streets thanks to the permanent installation of dozens of display cases containing glass artefacts. A major event took place in 2015 when the Toyama Glass Art Museum opened to the public. The museum building designed by the famous Japanese architect Kengo Kuma combines an exterior of a cool, modern high-tech look with a fascinating traditional wooden structure located inside. The museum runs a remarkable public collection of international glass art, including numerous Czech artefacts, and not only organizes it exhibitions (e.g. several solo presentations of Czech artists, among them the renowned artists Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová), but also the triennial Toyama International Glass Exhibition.

From the very beginning, the management of the Toyama institute entrusted the Americans with art and craft work with hot glass in the smelter, while the cut and engraved glass was managed by the Czechs. This division, in fact, corresponds with the way the two respective glass-making superpowers are generally perceived by the glass-making community. The choice was also based upon the reputation that the Czech ‘art glass’ has held since the end of the 1950s (the American one, respectively, since the 1960s). The school had invited the Czech professor Vladimir Klein to cooperate in 1991, which proved to be an extremely good choice. After his four years of operation, other Czech artists were able to gradually follow up on his activities, namely František Janák (1995–1997), Josef Marek (1997–2000), Pavel Mrkus (2000–2004), Pavel Trnka (2004–2008), Lada Semecká (2008–2012), Stanislav Müller (2012–2016), Václav Řezáč (2016–2019) and, last but not least of the nine, Jaroslav Šára.

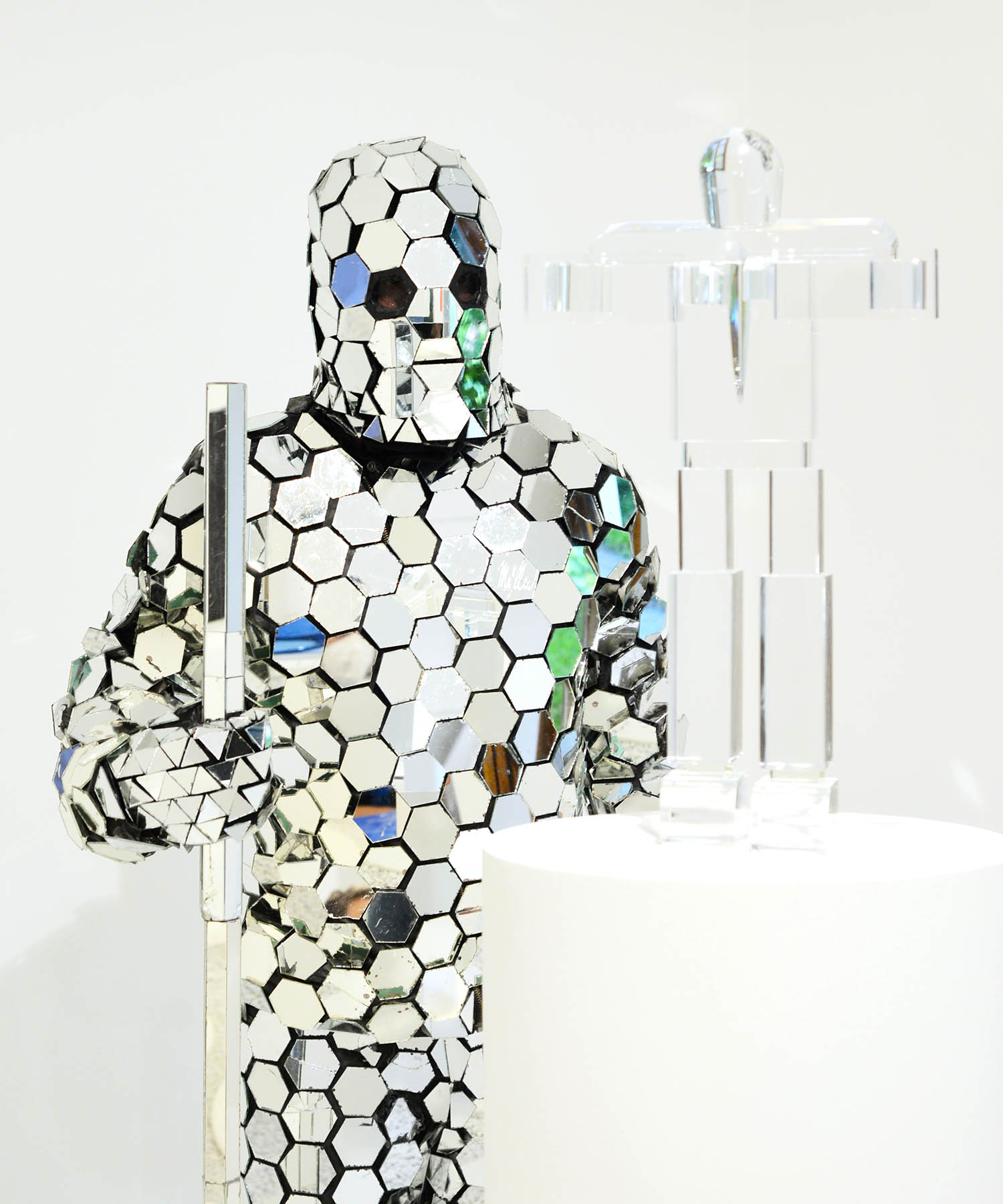

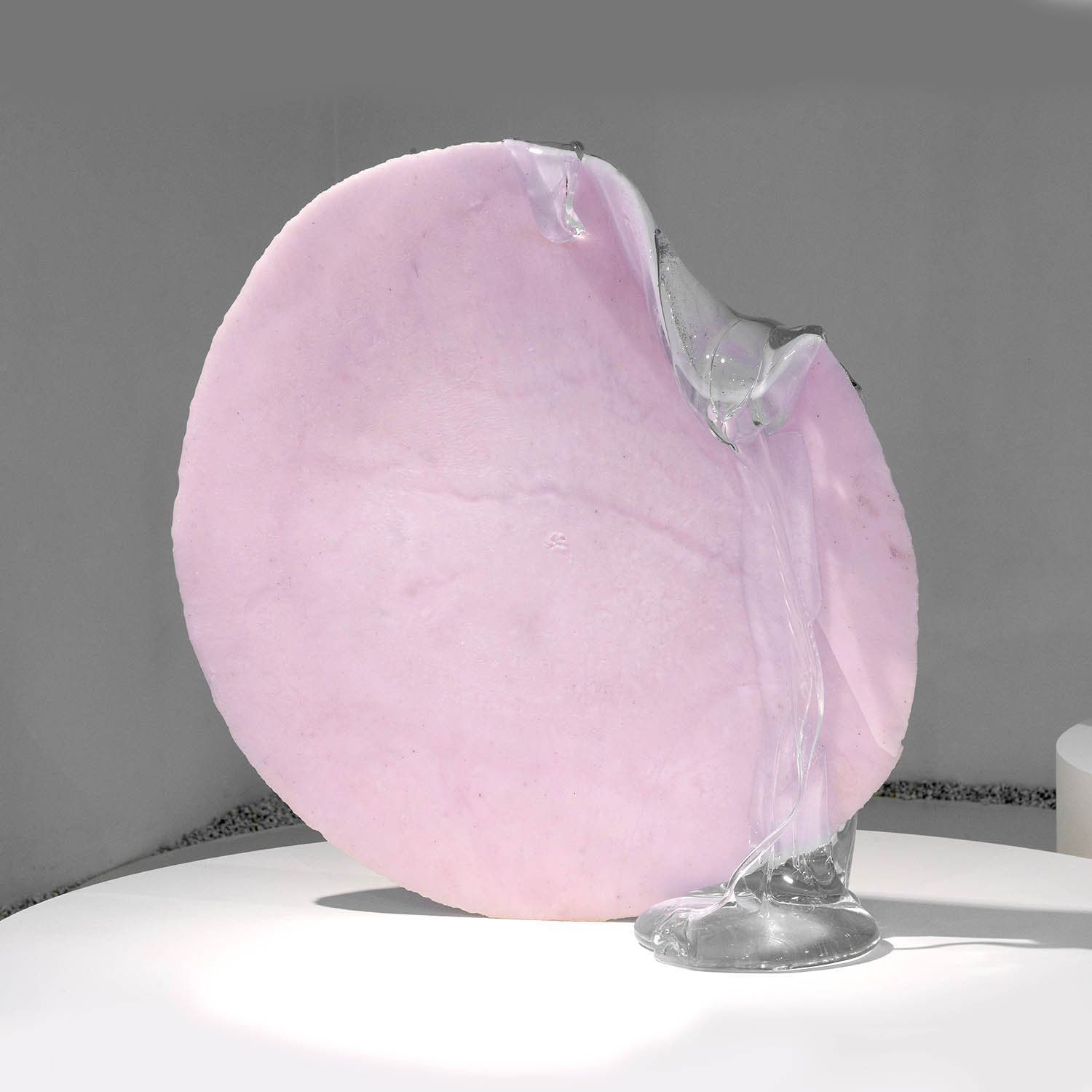

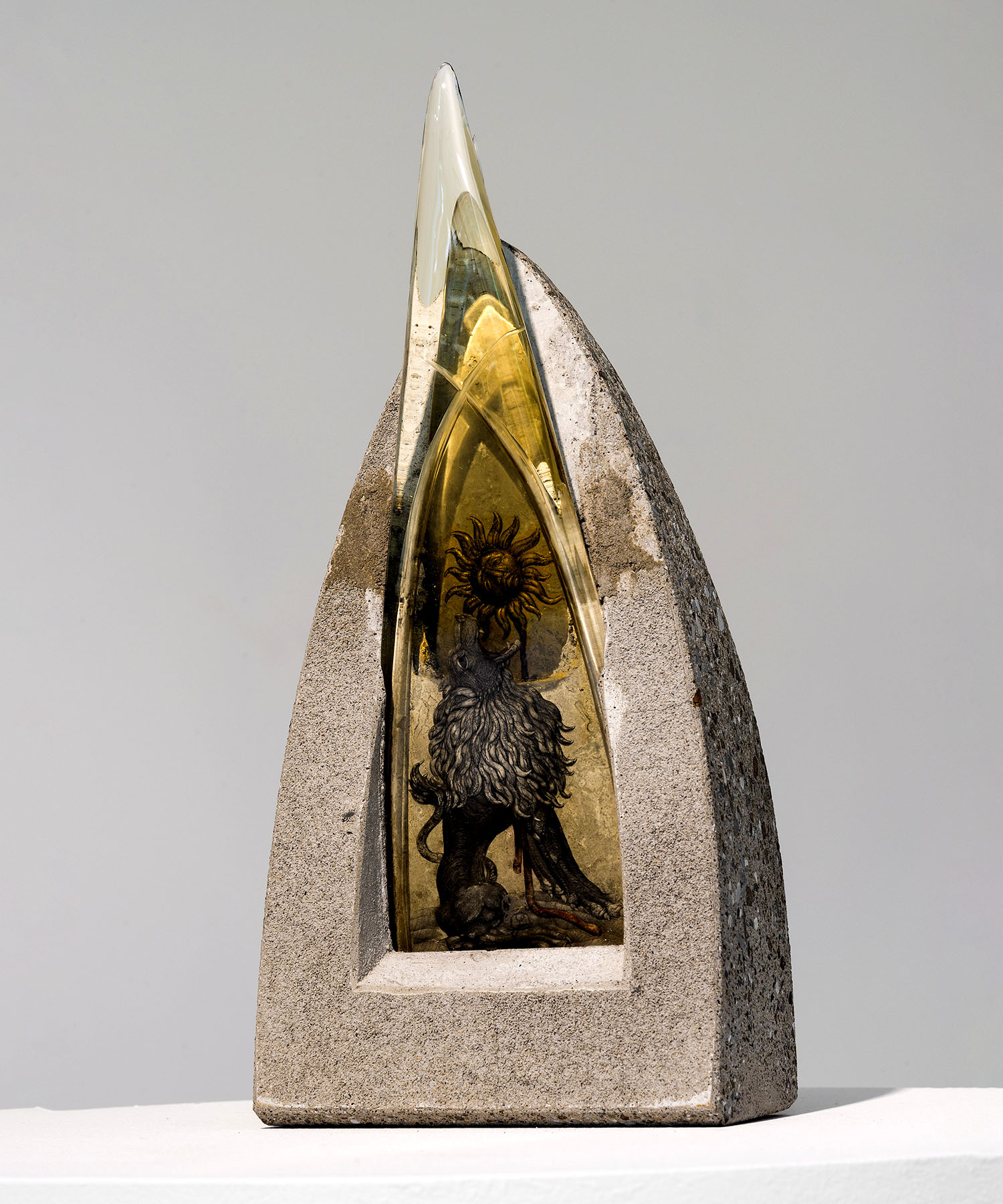

These Czech artists received interesting and important inspirations from their internships in Japan, and these impulses have become the focus of the present exhibition Greetings from Toyama. Exploiting his Japanese experience, Vladimir Klein (*1950) have enriched his earlier creative way of processing most of his works with themes such as lamps, fish and the elements, to which he added a unique glass-processing innovation, chopping, which he uses to this day. While in Japan, František Janák (*1951) began to focus on the technique of molten sculpture, which opened up new opportunities for artistic expression to him, including the application of colours. During his stay in Japan, where many of his works were created, he wrote highly engaging, but often rather critical reports for Umění a řemesla (Arts and Crafts) magazine. Although the earlier works by Josef Marek (*1963) used to be full of contrasts, and sometimes very rough at that, the artist seems to ‘have gone romantic’ after his return from Japan. He added colours and sometimes softer outlines, and discovered the theme of a circle for himself. Pavel Mrkus (*1970) is an artist who was fascinated by Japanese Zen gardens, whose character he transferred to glass-mirrored objects made of flat and cut glass. He became interested in video art and optical-acoustic installations, in which his life in the Far East played an important role. He has achieved considerable success in this field of art. In Japan, Pavel Trnka (*1948) transposed the colours, a theme continuously exploited and masterfully treated by him in glass-making, into abstract geometric paintings. He continues his research on the topic of colours in connection with his artistic glass-making and painting activities. During her stay in Japan, Lada Semecká (*1973) developed her extraordinary artistic sensitivity. The change in the rhythm of her life there led her to an even finer perception of natural events, sounds and silence. Stanislav Müller (*1971) introduced his Mirror Man, a fictive character which was created in the mid-1990s based on impulses from Japanese manga to Japan. During the artist’s stay in Toyama, however, Mirror Man’s performances gained a new dimension in direct contact between the two cultures. In Toyama, Václav Řezáč (*1977) began a completely unique and bold combination of two seemingly disparate techniques: glass molten in a mould, and cast from a glass-melting crucible. In the works resulting therefrom, the exact shapes collided in contrast with the amorphous flowing matter. He has transferred the new technology to the Czech Republic and further cultivates it artistically. The gifted artist and engraver Jaroslav Šára (*1981) from Nový Bor has been to Toyama for only two years now and only the future will show to what extent will this experience expand his artistic expression.

The difficulties the Czech professors experience from encounters with a different mentality, social behaviour and way of life, a fixed hierarchy of job positions, a different organization and the rhythm of work are balanced by the immense diligence and purposeful determination of their Japanese students. At the same time, they struggle to teach them to think more freely, not to be bound by customs and rules; they have to try and arouse their desire to express their thoughts through glass without fear and, at the same time, to be able to distinguish these thoughts from mere impulsive ideas. Of course, they passed on to their Japanese students their knowledge of traditional Czech glass-making technologies and an insight to how to exploit them independently for further development. They established lasting friendships and cooperation and, by their example, they enabled a number of other artists and curators to host, lecture and lead workshops to which they are regularly invited to Toyama.

Over the years 1991–2021, the nine Czech artists have established an important platform, in many respects absolutely extraordinary and unique by its character of the mutual influence and intertwining of the respective cultures of Europe and the Far East.

Dr. Milan Hlaveš, Exhibition Curator